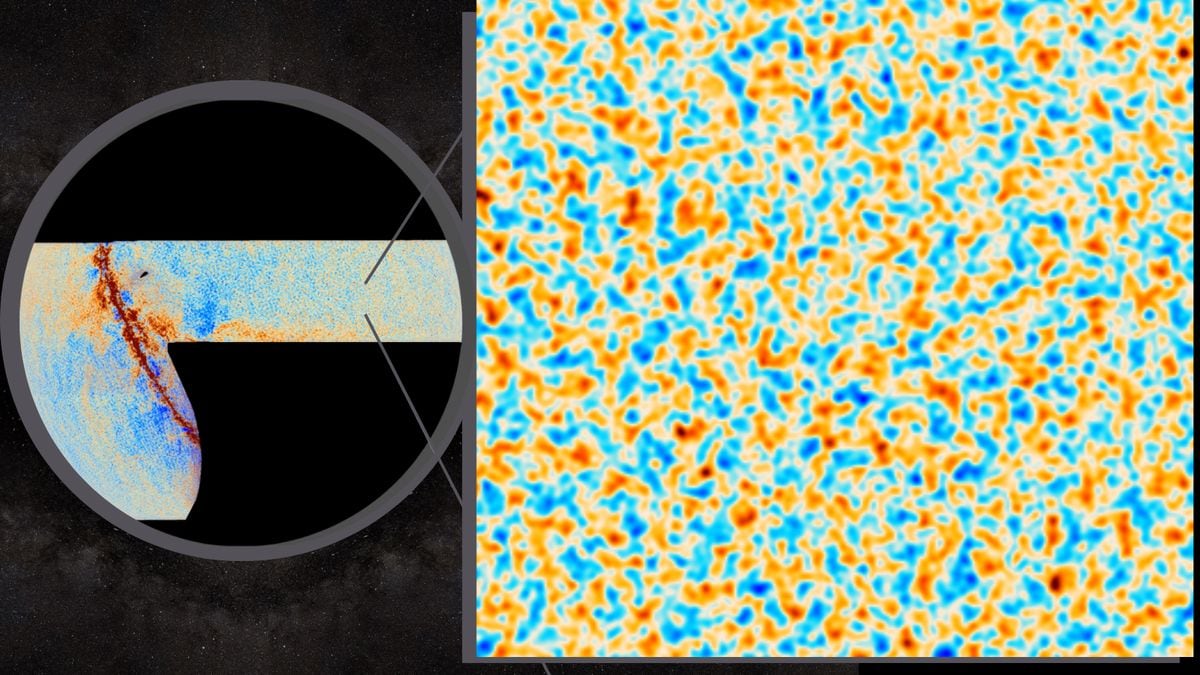

New images from the now-decommissioned Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) provide the most precise glimpse yet of the universe just 380,000 years after the Big Bang. These images of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), captured before ACT ceased operations in 2022, reveal how the first structures that would later form stars and galaxies began taking shape.

Breakthrough in Understanding Early Cosmic Structures

According to reports, the images depict the intensity and polarisation of the earliest light with unprecedented clarity, validating the standard model of cosmology. Researchers found that these findings align with previous observations, reinforcing current theories on the universe’s evolution. The data also reveal the movement of ancient gases under gravitational influence, tracing the formation of primordial hydrogen and helium clouds that later collapsed to birth the first stars.

ACT director and Princeton University researcher Suzanne Staggs said in a statement that they are seeing the first steps towards making the earliest stars and galaxies. They are seeing the polarisation of light in high resolution. It is a determining factor distinguishing ACT from Planck and other earlier telescopes, she added.

Imaging the Universe’s First Light

As per reports, before 380,000 years post-Big Bang, the universe was opaque due to a hot plasma of unbound electrons scattering photons. Once the universe cooled to approximately 3,000 Kelvin, electrons bound with protons to form neutral atoms, allowing light to travel freely. This event, known as the ‘last scattering,’ made the universe transparent, leaving behind the CMB—a fossil record of the first light.

ACT, positioned in the Chilean Andes, captured this ancient light, which has been traveling for over 13 billion years. Previous studies from the Planck space telescope provided a detailed image of the CMB, but ACT’s data offers five times the resolution and improved sensitivity.

Insights into Cosmic Evolution and Expansion

The high-resolution images also track how primordial hydrogen and helium gases moved in the universe’s infancy. According to reports, variations in the density and velocity of these gases indicate the presence of regions that eventually formed galaxies. These fluctuations, frozen in the CMB, serve as markers of the universe’s expansion history.

Using ACT data, researchers also estimated the universe’s total mass, which is equivalent to around 2 trillion trillion suns. Sources report that approximately 100 zetta-suns of this mass consist of ordinary matter, while 500 zetta-suns correspond to dark matter, and 1,300 zetta-suns are attributed to dark energy.

Addressing the Hubble Tension

One of the biggest challenges in cosmology is the discrepancy in measuring the universe’s expansion rate, known as the Hubble tension. Measurements from nearby galaxies suggest a Hubble constant of around 73-74 km/s/Mpc, while CMB observations, including those from ACT, yield a lower value of 67-68 km/s/Mpc.

Columbia University researcher Colin Hill, who studied the ACT data, told that they wanted to see if they could find a cosmological model that matched the data and also predicted a faster expansion rate. He further added that they have used the CMB as a detector for new particles or fields in the early universe, exploring previously uncharted terrain.

However, reports confirm that ACT findings align with prior CMB-based measurements, offering no evidence for alternative cosmic models that could explain the discrepancy.

Looking Ahead

ACT concluded its observations in 2022, and astronomers have now shifted focus to the Simons Observatory in Chile, which promises even more advanced studies of the universe’s early light. The new ACT data has been made publicly available through NASA’s LAMBDA archive, with related research published on Princeton’s Atacama Cosmology Telescope website.