Omar Marques | Lightrocket | Getty Images

On a Sunday in early March, Dr. Angeli Maun Akey noticed something peculiar while making payroll for her private practice in Gainesville, Florida: She was missing $19,000.

Akey owns and operates a primary care practice that serves around 3,500 patients in the area, many of whom suffer from chronic diseases. She opened in 2000 and manages a staff of nearly 20 people. Over the last two decades, Akey said, her practice and patients have been like an extension of her family.

“There’s no better life,” she told CNBC in an interview.

When Akey first noticed the discrepancy in her cash flow, she thought the funds had been embezzled, something she said she’s experienced three times since graduating from medical school. But after searching online, Akey realized she had a much bigger problem.

The health-care technology company Change Healthcare had been breached in a cyberattack.

Change Healthcare offers payment and revenue cycle management tools, and other solutions such as electronic prescription software. On Feb. 21, UnitedHealth Group, which owns Change Healthcare, discovered that hackers compromised part of the unit’s information technology systems.

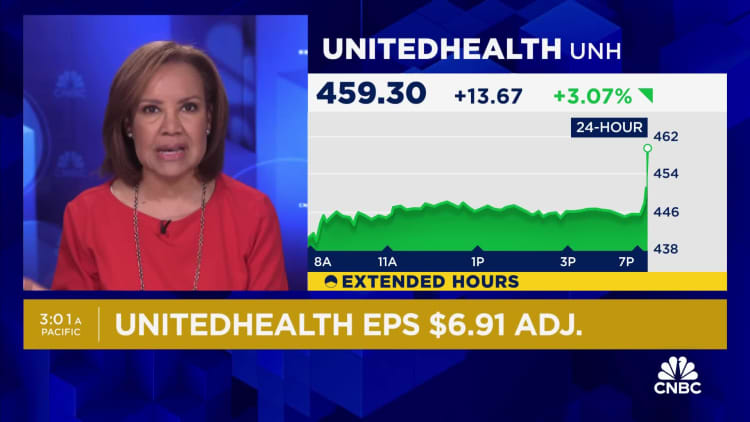

UnitedHealth said in a filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission that it isolated and disconnected the impacted systems “immediately upon detection” of the threat. In its first-quarter earnings report in April, UnitedHealth said the total cost of the cyberattack could be as much as $1.6 billion for the full year. The company’s stock is down nearly 8% year to date.

The disruption has caused severe fallout across the U.S. health-care system, as many doctors such as Akey were temporarily left without a way to get paid for their services.

Akey said the outages from the cyberattack reduced her practice’s cash flow by more than 80% for six weeks. As of early April, she said, she had amassed more than $130,000 worth of insurance claims that she had not been able to get reimbursed for.

Making payroll quickly became a major concern, and Akey said she stopped paying her own salary to help support her staff. Her bank offered her a loan to keep her practice afloat, but it came with an 11% interest rate. Akey said she felt it was too high.

She turned to her patients for help, asking for voluntary $45 advances that would be repaid.

“I’ve had patients for like a quarter century, so a lot of them have been like, ‘No, no, I need to give you more.’ So there’s $100 checks, $200 checks, $500 checks, $2,000 checks,” Akey said. “They have had 0% responsibility for this situation, and they’re fronting the money to keep us going.”

Earlier this month, Akey liquidated her retirement investments as an extra precaution. She said she was feeling frustrated and vulnerable, especially as rumors were swirling about the possibility that a second breach had occurred. UnitedHealth told CNBC earlier this month that there is “no evidence of any new cyber incident at Change Healthcare.”

“I just decided I can’t do this again,” Akey said.

UnitedHealth said in an April 22 press release that it has been working to bring systems back online, and that Change Healthcare has made “continued strong progress.” Medical claims across the U.S. are flowing at “near-normal levels,” and payment processing by the company is at more than 85% of pre-incident levels, the release said.

“We know this attack has caused concern and been disruptive for consumers and providers and we are committed to doing everything possible to help and provide support to anyone who may need it,” UnitedHealth CEO Andrew Witty said in the release.

Akey said payments have begun flowing back into her practice, though levels are still down between 30% and 40% from where they normally are.

She said the restarted payments have lifted a “humongous weight” off her back, but the road ahead will be difficult. Even so, she thinks her practice will be able to pull through, and she will be able to restore her retirement investments some time in the next few months.

“We love our patients, and that’s why I’m fighting so hard,” Akey said.

A quiet health-care giant

UnitedHealth Group Inc. headquarters stands in Minnetonka, Minnesota, U.S.

Mike Bradley | Bloomberg | Getty Images

Change Healthcare is not a household name for most Americans and even many health-care workers. Much of the company’s technology helps facilitate billing, payments, benefits evaluations and information exchanges behind the scenes.

Change Healthcare is the largest U.S. clearinghouse for medical insurance claims. A clearinghouse is like a middleman for the transactions between providers — such as doctors, hospitals and pharmacies — and payers — such as insurance companies, Medicare and Medicaid.

A clearinghouse helps deliver the right bills to the correct payers. It’s just one of the ways Change Healthcare touches cash flow within the health-care sector.

The company operates on an enormous scale. Change Healthcare processes more than 15 billion billing transactions annually, and 1 in 3 patient records passes through its systems, according to its website. That means Change Healthcare’s reach extends beyond UnitedHealth’s already sizable customer base.

Money stopped flowing when the company’s systems were disrupted due to the cyberattack, and a major source of revenue for thousands of providers across the U.S. screeched to a halt.

It’s caused a lot of sleepless nights for Dr. Barbara McAneny.

McAneny founded a multidisciplinary private practice with another physician in New Mexico in 1987. The practice now supports a staff of 280 people and offers a range of services, including cancer care. She also served as the president of the American Medical Association, or AMA, a research and advocacy group that represents physicians, from 2018 to 2020.

McAneny said she had tried to prepare for the possibility of a cyberattack, so the practice had contingency plans and funds stashed away to cover payroll and other expenses. However, she said she had “no idea” how she could have prepared for a breach of this magnitude. The practice felt the effects immediately.

“The cash flow for the practice went to zero that day,” McAneny told CNBC in an interview.

She said the practice’s partner physicians stopped taking a salary, and they told employees that they couldn’t approve overtime pay. Expenses became a real concern, but her “major fear” was whether the practice could continue purchasing chemotherapy for the cancer patients who rely on it for treatment.

McAneny’s practice buys chemotherapy from group purchasing organizations, or GPOs. It continued to place orders in the weeks following the cyberattack. But while Change Healthcare was down, there was no money to pay for the treatment. By April 10, the practice owed more than $6 million for chemotherapy alone.

“If the flow of chemotherapy stops from the GPOs that supply our chemotherapy, people will die,” she said.

McAneny said she lived in fear that supply would dry up. The thought had been waking her up in a cold sweat at night.

By mid-April, money started trickling back into McAneny’s practice, and it began chipping away at its $15 million claims backlog. She said claims started moving substantially in the last couple of weeks but that the practice’s cash flow is still only around 70% to 80% of what it normally is.

McAneny said the practice is “significantly in debt,” which will take several months to resolve. She said she is very worried about late fees. Even so, signs of progress have come as a relief.

“I might actually sleep through the night,” she said.

Funding assistance

Early in March, UnitedHealth launched a temporary funding assistance program to help support providers that have experienced cash flow disruptions due to the cyberattack. There are no fees, interest or other costs on top of the payments, and providers have 45 days to repay the funds once standard payment operations resume.

Eligible providers will get funds weekly, and the amount they get is based on the difference between their historical weekly claims or payment volume before the breach vs. after, according to the website.

UnitedHealth said it only has “partial visibility” into most providers’ histories and may be “unable to see the full impact of their needs.” Providers could see a gap in their funding amounts and, if they do, they are encouraged to submit a temporary assistance inquiry form through the website for additional support.

But for doctors such as Akey, the program has been a source of frustration. As of Thursday, Akey said she had been approved for around $31,000 worth of funding. She called the total “woefully inadequate” and said it amounts to less than two weeks of help.

Akey said Tuesday she was not aware she could have applied for additional funding support, despite reading the website and making repeated attempts to contact UnitedHealth.

Sarah Carlson, who owns and operates a marriage and family therapy practice in Boulder, Colorado, had a similar experience with the funding program.

Carlson’s practice amassed a $75,000 claims backlog by early April because of the cyberattack, she told CNBC. She said she had been fronting her employees her own money to make payroll, and after a couple of sleepless nights, she decided to temporarily stop accepting some new clients.

Carlson applied for UnitedHealth’s funding assistance program, but she said the payments up to that point had been negligible. One week, she said, she received just $10.

“It was comical. Literally, I think I laughed,” Carlson said in an interview.

UnitedHealth told CNBC that Carlson had not applied for additional funding. Carlson said she thought she had done so by filling out a new form, separate from her initial application, with information about the total amount of claims she was owed.

McAneny said that as of mid-April she had around $28,000 from UnitedHealth sitting in an account, which is only enough to cover the cost of about two drugs.

“It was useless to me,” she said.

McAneny has since applied for and received additional funding. She said she is using that money to help pay off the chemotherapy bills.

UnitedHealth told CNBC in a statement Tuesday: “We have issued more than $6.5 billion in assistance to providers and we continue to encourage any provider to reach out and our goals has always been to help get the word out to as many providers as possible here.”

A controversial merger

Sheldon Cooper | Sopa Images | Lightrocket | Getty Images

UnitedHealth’s ownership of Change Healthcare has raised eyebrows from the outset.

The company has two major business units: Optum and UnitedHealthcare. Optum offers a range of pharmacy services and consulting services and provides medical care for around 103 million consumers, while UnitedHealthcare provides insurance coverage and benefit services to more than 55 million people globally, according to the company’s website.

UnitedHealth’s reach is already substantial, so when it announced that Optum and Change Healthcare had agreed to combine in January 2021, it alarmed organizations such as the AMA.

The AMA sent a letter to the U.S. Department of Justice in April 2021 arguing the $13 billion deal would have “significant anticompetitive effects” on doctors, hospitals and insurers. The group urged the DOJ to look at the merger.

The DOJ sued to block the deal the following year, arguing that UnitedHealth’s proposed acquisition would harm competition in the sector. The suit was unsuccessful, and Optum announced that it completed its combination with Change Healthcare in October 2022.

In UnitedHealth’s quarterly call with investors in April, CEO Andrew Witty said the company’s ownership of Change Healthcare is “important for the country.” He said the cyberattack likely would have happened either way, but if UnitedHealth did not own the company, Change Healthcare would not have had the resources or support necessary to bring its systems back online.

“We’re going to bring it back much stronger than it was before,” Witty said.

The AMA has also been outspoken about the cybersecurity breach. In a letter to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in March, for instance, the organization said it is concerned about the “undue financial hardships facing physician practices” if the cyberattack was not resolved quickly. The AMA said it is particularly concerned about small, rural and less-resourced practices, according to the letter.

In late February, the DOJ launched an antitrust investigation into UnitedHealth, according to a report from The Wall Street Journal. The investigation is exploring issues such as its doctor group acquisitions and the relationships between Optum and UnitedHealthcare, the report said. UnitedHealth declined to comment on the matter during its investor call.

The DOJ declined to comment.

‘It’s a mess’

UnitedHealth Group signage is displayed on a monitor on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

Michael Nagle | Bloomberg | Getty Images

There’s no quick fix for providers affected by the breach. Switching to another clearinghouse can take weeks to months, and submitting claims manually creates mountains of extra work for practices that are often already overwhelmed with administrative and clerical tasks. Some payers don’t even accept paper claims anymore.

“It’s not been fun,” said Dr. Tyler Kisling, who with his wife owns and operates an orthodontic and pediatric dentistry practice in California.

Kisling said the pair have taken out around $20,000 from their personal savings to help keep things afloat since the cyberattack. The breach has created a lot of stress, Kisling said, and he’s resorted to printing out paper calendars to help keep track of bills and due dates.

The company that operates their practice’s patient management software has worked to get set up with another clearinghouse, but as of April 19, Kisling said it was still not running. The workaround has been to fill out all of the practice’s claims by hand, put them in envelopes and mail them off to insurers. Kisling said the task has been like a new full-time job.

Payments are just starting to trickle in, and Kisling said he thinks it is largely because the practice took steps to mail in claims. There’s still a long road ahead.

“I just don’t know how much longer it’s going to take to catch up with all the backlog,” he said.

McAneny said her practice switched to another clearinghouse during the breach but that they all have different peculiarities that can be difficult to work out. She said she had 5,000 rejected claims in a week, which meant the practice had to go through each one to determine what needed to be fixed.

“The comma goes here, or the date of birth goes over there or whatever they want,” she said.

McAneny said it’s been a “huge amount” of work. Her billing staff has been working a lot of overtime.

Dr. Purvi Parikh, an allergist and immunologist with a private practice in New York City, said her practice reconnected with Change Healthcare after seven weeks of outages. It was a welcome sign of progress, especially because Parikh and the other doctors who own the practice had been covering payroll and expenses out of pocket.

But figuring out how to file seven weeks’ worth of claims has been draining for Parikh’s staff and the practice’s already diminished resources.

“It’s such a waste of everyone’s time,” she told CNBC in an interview. “We spend hours and hours, or even days, trying to figure out where to get money from, how to now resubmit through a new clearinghouse, and then resubmit again back through Change Healthcare. It’s a mess.”

UnitedHealth told CNBC that it has been working to communicate with providers, government officials, health systems, trade associations and customers about the breach from the outset.

The company said it has provided updates through Change Healthcare’s product website, and it launched a separate website about its response to the cyberattack that has received millions of page views. UnitedHealth said it also launched a multimillion-dollar social media and digital campaign to raise awareness about its funding assistance program.

Additionally, UnitedHealth has hosted calls with security executives, providers, customers and advocacy groups that have been attended by thousands, the company said.

Nevertheless, some providers said getting information about the breach has been challenging.

As of mid-April, Parikh hadn’t been able to get anyone from Change Healthcare on the phone. She said she was getting all her information directly from her billing company. There has been “zero communication” from UnitedHealth, Optum or Change Healthcare, she said.

Kisling said his office received no formal notification about the breach, and that he heard about it in the media. His office manager had to call one of the practice’s software vendors to ask what was happening.

“We all just kind of had to figure it out on our own,” he said.

Many doctors have been leaning on one another to share information and tips about how to handle the breach. On platforms such as Doximity, which is a medical website used by more than 80% of U.S. physicians, doctors have been “exchanging notes” about how they’ve managed, said Dr. Amit Phull, the chief physician experience officer at Doximity.

Phull said there were a lot of people posting about the breach who didn’t know what to do. Initial feelings of “bewilderment” quickly progressed to anxiety, fear and anger, he said.

Providers are left with questions

Igor Golovniov | Sopa Images | Lightrocket | Getty Images

UnitedHealth said in late February that the ransomware group Blackcat was behind the cyberattack. Blackcat, which also goes by the names Noberus and ALPHV, steals sensitive data from institutions and threatens to publish it unless a ransom is paid, according to a December release from the DOJ.

The company said its investigation into the breach is ongoing, and it could be months before the company can identify and notify affected individuals. UnitedHealth is working with law enforcement officials, cybersecurity experts and regulators to assess the breach, according to its website.

On April 22, UnitedHealth told CNBC that it paid a ransom in an effort to protect patient data. It did not specify the amount. The company also confirmed that files containing protected health information and personally identifiable information were compromised.

Providers have been left with questions about what happens next.

“How are they going to keep this from happening in the future?” said John Bieda Jr., who owns and operates a marriage and family therapy practice in California.

Bieda said he founded his practice with funds he inherited from his parents after they died. He told CNBC he is very proud of what he has built, and he wishes his father were around to see it. But he said his experience with the Change Healthcare breach has left him feeling lost, and at times like he does not want to own his own company anymore.

As of Friday, Bieda said he had around $109,000 of claims outstanding. He has taken $241,000 out of his retirement accounts to keep the practice afloat.

“I have been on the verge of tears significantly,” Bieda said. “It just is devastating.”

McAneny said many providers have opened lines of credit due to the breach, which raises questions about how UnitedHealth will address problems around interest, late fees and damage to credit ratings.

“They’ve caused a lot of harm to a lot of practices,” McAneny said. “How are they going to make up for the losses that we have had?”