President Joe Biden spent much of his third year in the White House trying to brag about what he’d done for the American economy.

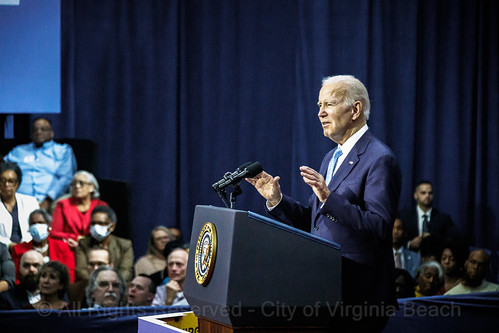

In February, speaking to a chapter of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers in Maryland, hedeclared, “For the past two years, we’ve been carrying out my economic plan that grows the economy from the bottom up and the middle out, not the top down.” Biden then recited a laundry list of economic indicators. The unemployment rate was 3.4 percent. Gas prices had dropped by $1.60 per gallon. In his first two years in office, he said, “we created 800,000 new manufacturing jobs.” Inflation was down from its peak, and take-home pay was up. “We’ve got more to do, but I’m telling you, the Biden economic plan is working because of you all,” he said, pausing for applause. “And I really mean it.”

This was typical of Biden’s prepared public remarks. In at least a dozen speeches and statements in 2022 and 2023, the president referred to either “my economic plan” or “the Biden economic plan,” crediting himself and his administration with the state of the economy. “My economic plan is showing results,” he said in a preparedstatementin November 2022. “My economic plan is working,” hesaidin July 2023.

In summer 2023, Biden finally gave that plan a name. Or rather, he adopted the name his critics had already used to describe his policies: Bidenomics.

The term had begun as a derisive label for the president’s economic foibles. An unsigned July 2022 editorial inThe Wall Street Journalbore the headline “Bidenomics 101.” It took issue with Biden’s public demand that “companies running gas stations and setting prices at the pump” bring down their pricesa sort of Nixonian jawboning where you respond to inflation by trying to bully companies into keeping prices low. The president, the editorial charged, “doesn’t appear to know anything about how the private economy works.”

Nearly a year later, in a speech in Chicago, Biden set out to claim Bidenomics as his own. The president framed his approach as “a fundamental break from the economic theory that has failed America’s middle class for decades now.”

Rather than “trickle-down economics” that helped only the already well-off, Biden said, he was pursuing an economic agenda that rejected the “belief that we should shrink public investment in infrastructure and public education.” He touted his record,crediting three major laws he’d signedthe American Rescue Plan (ARP), the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the Inflation Reduction Actwith helping to set the U.S. economy on a better track. “Guess what?” he said. “Bidenomics is working.”

Biden’s speeches were defensive in tone, and for a reason: Voters have consistently reported broad unhappiness with the economy. Surveys find low support for Biden’s handling of economic policy across nearly every demographic, including the younger voters and minorities who are typically Democratic stalwarts. The president’s embrace of Bidenomics was an attempt to convert skeptics into believers by arguing, more or less, that the economy was actually pretty great and that this was because of him and his policies.

The Bidenomics push was best understood as a messaging strategy rather than a shift in policy vision; the White House memo announcing the Chicago speech was crafted by two political messaging operatives rather than anyone on the administration’s policy team. But it did capture an underlying policy vision, a distinct approach to the economy that came to the fore during Biden’s first term. That vision had many facetspandemic aid, industrial policy, handouts for labor unions and public workersbut in many ways, it could be reduced to a single, overriding response: government spending.

Bidenomics was, at heart, a philosophy of throwing money at programs, people, political allies, and favored constituencies. That spending contributed directly and significantly to the rapid rise in inflation that helped fuel voter dissatisfaction with the state of affairs. Thanks to misallocation, poor implementation, and self-contradictory regulatory requirements, the substantive public payoffs to that spending have been weak at best and counterproductive at worst. Empowered Workers

In his Chicago speech, Biden framed the ARP as part of Bidenomics’ goal of “empowering American workers.” That was a shift from when he first pitched the legislation in January 2021.

Initially, Biden described the ARP as pandemic relief, with a particular emphasis on giving vulnerable Americans resources for dealing with COVID-19. “From big cities to small towns, too many Americans are barely scraping by, or not scraping by at all,” the White House’s announcement said. “And the pandemic has shined a light on the persistence of racial injustice in our healthcare system and our economy.”

By the time Biden entered office, Congress, under President Donald Trump, had already passed about $4 trillion worth of pandemic spending. For Biden, that wasn’t enough. Prior pandemic spending was “a step in the right direction” but “only a down payment” that “fell far short of the resources needed to tackle the immediate crisis.”

In his first weeks in office, Biden proposed a $1.9 trillion spending package. Like previous rounds of pandemic aid, it would be funded via the deficitby borrowing rather than raising tax revenue or cutting spending elsewhere. He rejected a counterproposal from congressional Republicans that would have totaled about $620 billion. Biden offered few specifics as to why that figure was insufficient, but he insisted the real risk was in passing a spending package that was too small. In a meeting with the Republicans proposing the smaller alternative, White House spokesperson Jen Psakisaid, Biden said “that he will not slow down work on this urgent crisis response, and will not settle for a package that fails to meet the moment.” The new president was intent on goingwhich is to sayspendingbig.

“We are in a race against time,” the ARP announcement said, “and absent additional government assistance, the economic and public health crises could worsen in the months ahead; schools will not be able to safely reopen; and vaccinations will remain far too slow.”

Yet even at the time of passage, it was clear little of the ARP package would be spent on COVID relief. Less than 1 percent of the total was targeted specifically at vaccines. According to a contemporaneousanalysisby the nonprofit Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, less than 6 percent was earmarked for various containment and mitigation measurestesting and tracing, general investments in public health, funding for the Indian Health Service. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) noted that a $50 billion disaster relief fund, nominally targeted at pandemic mitigation, could be used on other unrelated disasters as well, and that only half of it would likely be spent by the end of 2022, suggesting that a large portion would go toward something other than immediate pandemic emergencies.

Meanwhile, one of the largest pots of money, about $350 billion, was directed at state and local governments, who were under no obligation to spend it on the pandemic. This funding was included at the behest of lobbies representing those governments, such as the National League of Cities, which projected a $360 billion shortfall in local governments as a result of a pandemic-induced fiscal crunch. From the outset, those estimates were obviously self-serving: In 2020, even as the pandemic upended so much economic activity, state revenue was upabout 7 percentfrom pre-pandemic levelsand that’s not counting the billions in state and local aid that Congress authorized before Biden entered office.

So it was hardly surprising when most states were eventually flush with cash. California took $26 billion in ARP funding; months after the law passed, the governor’s office reworked its budget to account for $76 billion in previously unexpected tax revenue. By March 2023, the Government Accountability Office reported, less than half of the state bailout money had been spent, ighlighting how unnecessary that assistance had been. Some of the money thatwasspent, meanwhile, went tobailing outlong-struggling government-owned golf courses in New Jersey and California.

The ARP also authorized about $130 billion worth of spending on public schools. This was ostensibly a COVID relief measure, but the funding could be spent for purposes that had nothing to do with the pandemic. Those billions arrived after two previous infusions of pandemic relief that had allocated a total of $71 billion for schoolsalmost none of which had been spent, suggesting that a lack of money was not the primary problem.

Indeed, many schools remained closed for in-person education even into 2022, mostly in blue states. The chaos in public education not only left parents scrambling for alternatives; it damaged a generation of children. National test scores showed that even in the aftermath of the pandemic, student testscoreson reading and math continued to drop, reaching their lowest levels in decades.

What drove the longest school closures? Teachers unions, which lobbied aggressively for the school funds in the ARP and, at the same time, pressed relentlessly to keep teachers from being required to return to classrooms. In his Chicago speech, Biden reiterated a frequent promise to be the “most pro-union president in history.” In this one way, he could indeed be said to have empowered a very narrow, very specific class of American worker. Infrastructure Deficit

The American Rescue Plan was passed along partisan lines, without any fiscal offsets. For his next act, Biden would reach across the aisle with what became known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) or, more formally, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

When the BIL passed in late 2021, the White House issued a self-congratulatory statement calling it “a once-in-a-generation investment in our nation’s infrastructure and competitiveness” while taking a shot at officials who for too long “have celebrated ‘infrastructure week’ without ever agreeing to build infrastructure.” But the BIL itself was a deficit-spiking boondoggle that has so far failed to meet many of its own goals, funding incomplete projects and wasteful subsidies for favored constituencies.

The total cost of the law came in at $1.2 trillion, of which about $550 billion was new spendingthe rest was redirected or reauthorized, including about $200 billion that had initially been part of the ARP. (Just months earlier, Biden had pitched the ARP’s massive dollar figure as vital to pandemic relief. Now, apparently, much of it could be redirected.) As the spending package came together in summer 2021, the CBO estimated that it would add about $256 billion to the deficit. Other estimates found that its long-term increase in baseline spending on transportation meant the deficit increase would be closer to $400 billion.

Like so many large spending packages, the legislation was treated as a Christmas tree on which to hang tangential projects. Some of the bill’s “once-in-a-generation investments” included funding for unprovendrunk-driving-prevention technologyon cars, avaping ban on Amtrak, andnew reporting requirements for cryptocurrency.

Much of the funding was more directly targeted at transportation infrastructure. But that doesn’t mean it was well-spent.

For example, about $3 billion was allocated to California’s long-delayed, long-overdue high-speed rail project. Under the original plan, a 520-mile rail line was to connect San Francisco and Los Angeles by 2020. By 2023, only 170 miles of track had been completed and the line had been trimmed to connect Merced with Bakersfield, two smaller metro areas well over an hour’s drive from either of the originally planned endpoints. The project, initially funded by a bond of less than $10 billion, had run wildly over budget, with a projected final cost of $128 billion. By the time the infrastructure bill’s funds were awarded, the rail line had already received $20 billion in grants, including $2.5 billion as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Acta bill passed under President Barack Obama, way back in 2009. Biden’s infrastructure bill shoveled billions more at the train to nowhere.

The BIL also allocated about $7.5 billion for a nationwide network of charging stations to power America’s growing fleet of electric vehicles. These have been a priority for Biden since he took office, and,through an executive order, he had set a nonbinding target that 50 percent of all vehicles sold in the United States should be electric or plug-in hybrid by 2030. He also aimed to add 500,000 new charging locations.

Yet as of late December 2023, just one single charger in Columbus, Ohio, had come online with the billions provided by the infrastructure law. A few more are likely to open in 2024, but the sluggishness of the rollout demonstrates the law’s general inefficiency. Only a handful of states have even broken ground on the stations. Most have not even submitted proposals.

Part of the problem is that, in order to qualify for federal funding, the law initially required chargers to be built primarily with American-made products. Those Buy American provisions made infrastructure projectsslower, more expensive, and in some cases completely infeasible. Not long after the law passed, states expressed concern that the requirement could permanently stall charger construction, with transportation officials from Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming warning in a letter to the administration that “the programs could be particularly hard to implement in rural states if [the U.S. Department of Transportation] and [the Federal Highway Administration] do not implement the provisions with flexibility.”

In early 2023, the Biden administration waived the Buy American requirements for chargers produced and installed by October 2024. The waiver notice explained that it “enables EV charger acquisition and installation to immediately proceed.” It was effectively an admission that the law’s provisions had been at cross-purposes. An Act That Doesn’t Reduce Inflation

In 2021 and through 2022, U.S. inflation began to rise rapidly, hitting levels not seen in four decades. Although inflation increased in other developed countries as well, it ran higher in America, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco report issued in late 2021. In June 2022, year-over-year inflation peaked at 9.1 percent, and it remained at historically elevated levels for much of the rest of the year.

When the ARP was being debated, criticsincluding some economists associated with the Democratic Partyargued that its $1.9 trillion package, coming on the heels of the $4 trillion in deficit-financed pandemic emergency spending under Trump, was too large and too poorly designed, and it thus could cause inflation to spike.

One of the ARP’s biggest provisions was a series of “economic impact payments”checks of up to $1,400 per person for families making up to $150,000 annually, which is most families in the country. Those payments temporarily boosted American bank balances, which rose to record levels during 2021 and 2022, long after vaccines had become widely available and the most pervasive pandemic restrictions had been lifted. They also drove frenzied consumer spending, often for goods constrained by pandemic-related supply-chain restrictions.

Biden dismissed inflationary concerns, claiming in June 2022 that “the idea that [ARP] caused inflation is bizarre.”

In early 2023, three economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis published a report saying that pandemic spending played a “sizable role” in excess inflation. U.S. “fiscal stimulus during the pandemic contributed to an increase in inflation of about 2.6 percentage points,” they wrote. Pandemic spending wasn’t the sole cause of inflation, but it was a significant factor.

Public sentiment about the economy was sour, and inflation was the biggest cause. In May 2022, Bidendeclaredbringing down inflation would be his “top economic priority.”

At the time, Biden was negotiating an eve-shifting package of social spending that his administration had dubbed Build Back Better. Early estimates put the package’s total projectedcostat around $3.5 trillion. Over the course of negotiations, thanks in part to resistance from moderate Democrats, especially West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, that figure was whittled down to $1.7 trillion. The legislation was renamed in accordance with the president’s stated priorities: It was the Inflation Reduction Act.

The new moniker was entirely an exercise in political marketing. When the legislation was drawn up, the CBO’s nonpartisan economic analysts declared its impact on inflation would be “negligible.” The Penn Wharton Budget Model estimated the law’s impact on inflation would be “statistically indistinguishable from zero” and the law would cause the economy to actually shrink slightly in the first 10 years after passage, while growing slightly more by 2050.

It was dubbed the Inflation Reduction Act anyway. Presumably the Economy-Shrinking, No-Effect-on-Inflation Act of 2022 would have been a harder sell.

Inflation rates did decline over the following year, but this mostly meant that prices were rising less quickly rather than actually falling. While some Democrats tried to credit Biden’s policies for the slowdown in price increases, there was little reason to believe the Inflation Reduction Act played a meaningful role. “I can’t think of any mechanism by which it would have brought down inflation to date,” the Harvard economist Jason FurmantoldPBS.

Even Biden eventually seemed to agree that the law’s real purpose was unrelated to its name. A year after it passed, Bidendeclared at an August 2023 fundraiser that at least part of the Inflation Reduction Act “has nothing to do with inflation.” Rather, this $368 billion piece of the bill was “the single???largest investment in climate change anywhere in the world.” He added: “No one has ever, ever spent that.” Semiconductors Stall Out

Biden’s agenda extended into the realm of large corporate affairs. Here, too, was a contradiction: Sometimes he bragged about bolstering large corporate initiatives, while other times he called for cracking down on big businesses. In both modes, he struggled to achieve his stated goals.

Biden came into office as a proponent of industrial policyessentially, using federal subsidies and regulations to promote unionized factory production inside the United States. His biggest initiative on this front was the CHIPS and Science Act. Passed just days before the Inflation Reduction Act, it directed $76 billion to domestic manufacturing, with a particular emphasis on semiconductors, which are used to make computer chips. This included hefty subsidies for giant companies like Intel and Micron, providing public support to plants that were announced long before the CHIPS Act was passed.

Among the most prominent projects to benefit was a Phoenix microchip plant owned by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited (TSMC). In a December 2022 appearance at the still-under-construction facility, Biden declared, “American manufacturing is back, folks.”

But at the Arizona plant, which had been under construction since 2021, manufacturing hadn’t even started. Construction has been slow and has suffered from cost overruns. As with the Buy American mandate in the infrastructure law, a bevy of rules and regulations that applied to companies receiving CHIPS subsidies slowed down construction and development, undercutting the intended effect. Among the law’s provisions, for example, was a requirement that beneficiary companies provide on-site child care.

In 2023, just seven months after Biden’s speech at the Arizona plant, TSMC announced it would delay the start of chip production until 2025, blaming labor shortages.

Meanwhile, the president also issued a whole-of-government order pushing executive agencies to focus more aggressively on antitrust. He appointed Lina Khan, a young academic who had authored a headline-making 2017 paperarguing for breaking up Amazon, to head the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Khan proceeded to file major lawsuits against the tech giants Microsoft and Meta. The FTC lost both suits. In summer 2023, Khan’s FTC also launched a major lawsuit against Amazon.

Not all aspects of Bidenomics were directly related to spending. Biden also expanded the federal government’s regulatory reach. At the end of 2022, the Biden administration’s Unified Agenda, a guide to federal regulatory actions, listed 332 “economically significant rules,” a designation for rules estimated to have an economic impact of $100 million or more. According to the Competitive Enterprise Institute, which compiled the regulatory data, “Biden’s count of completed economically significant rules is higher than anything seen in the Bush, Obama, and Trump years.”

But Biden’s primary economic policy tool was spendingon unnecessary checks to Americans earning six figures, on school reopening funds that didn’t reopen schools, on charging stations that went unbuilt, on a semiconductor factory that hadn’t opened, on overbudget bullet trains, on an inflation reduction bill that wasn’t about inflation, on aid to state and local governments that didn’t need it.

“No one has ever, ever spent that” was about as useful and succinct an encapsulation of Bidenomics as one could find. Challenging Fiscal Outlook

The best case for Bidenomics is that, on paper, the American economy at the end of 2023 is doing fairly well.

Inflation rates have fallen steeply from their 2022 peak. Job growth remained steady throughout 2023, moderating slightly at the end of the year, with the unemployment rate remaining firmly under 4 percent. As the 2023 holiday season approached, consumers appeared to be pulling back on spending, but not so much that it would cause an economic downturn. Although a 2024 recession remains a possibility, many forecasters are optimistic the economy will achieve a “soft landing,” with inflation rates declining even as the economy continues to grow.

Yet there is little evidence Biden’s spending binge left the American economy better off. It’s not just that the spending contributed to inflation, pushing up prices on everyday necessities. The Fed responded to the inflation by raising interest rates, and that has gummed up the economy in many ways. New ventures predicated on rapid growth fueled by investment now have a much harder time securing funds. Slowdowns hit construction projects, with residential construction permitsfalling30 percent from the previous year at the start of 2023. They picked up somewhat later in the year, but only after crashing first. Higher interest rates shocked the housing market in other ways too, as existing homeowners resisted selling in order to keep older, lower-interest-rate mortgages.

The president periodically said he’d like to bring down housing prices. But under Biden, prospective homeowners have been saddled with the highest mortgage interest rates in years, making homeownershipalready exorbitantly expensive in many markets thanks to choked supply and regulatory burdenseven pricier for anyone who couldn’t afford to pay cash.

Then there was the debt and the deficit. In May 2022, Biden bragged he had reduced the federal budget deficitthe annual gap between spending and revenues. It was true that during Biden’s first years in office, the deficit came down from its pandemic peaks. But the drop was almost entirely due to expirations built into emergency spending. Biden was essentially boasting that he had allowed some temporary spending to expire as planned.

By 2023, the deficit wasn’t coming down anymore. The federal government ran a deficit of $1.7 trillion, up $320 billion from the previous year. The CBO released along-term budget forecastwarning of a “challenging fiscal outlook” driven by “large and sustained deficits,” leading to “high and rising federal debt that exceeds any previously recorded level.” The projected cause: “faster growth in spending than in revenues.” In short,spending.

Higher deficits, meanwhile, mean more spending on interest: “Risig interest rates and persistently large primary deficits cause interest costs to almost triple in relation to GDP between 2023 and 2053,” the CBO noted. Small wonder that Biden stopped bragging about the deficit.

Much of Biden’s presidency has been defined by this sort of memory-holing, when the president uses dubious evidence to give himself credit and then moves on when the story changes. Indeed, the wordBidenomicsitself eventually fell to this sort of revisionist political marketing.

After his Chicago speech, the president traveled the country making the case for Bidenomics. It wasn’t successful. Polls found that a clear majority of even Democratic voters were unhappy with the economy. In a NovemberNew York Times/Siena survey, just 2 percent of respondents rated the economy as excellent. Literally zero surveyed voters under 30 in the key swing states of Arizona, Nevada, and Wisconsin gave the economy top marks. Biden administration officials themselves seemed dismayed by the limited results of the president’s policies: In late 2023, an unnamed White House official told CNN the president was immensely frustrated about the slow rollout of infrastructure projects that Biden had hoped to show off.

Biden used the wordBidenomicsmore than 100 times in various speeches,accordingto NBC. But by late November, the term had entirely disappeared from his prepared remarks. Democrats had reportedly decided that their economic messaging would instead revolve around the more generic phrase “people over politics.” One marketing gimmick would be replaced with anotherbecause Bidenomics wasn’t working.